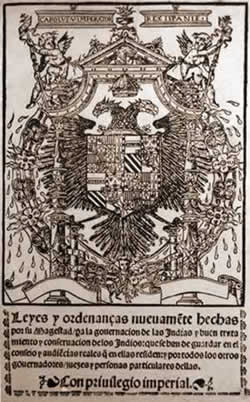

The New Indian Laws of 1542 or “New Indian Laws and ordinances newly made by their majesty for the governorship of the Indies and good treatment and conservation of Indians” are a compilation of the legislation that has been applied in the New World since the beginning of the conquest. This legislation was expanded with new rules and regulations with the aim of granting a legal framework and justifying the dominion of these lands, regulating the life of the population living in them and improving the living conditions of the indigenous people under the sovereignty of the Spanish crown.

But it was not only a compilation, but also an exhaustive revision and adaptation of the previous legislation to the new viceroyalty regime created with the New Laws, with its new institutions and its new territorial organization when the viceroyalty of Peru was created and the real Audiencias de Lima y de los Confines. From a social point of view, the most important measure was the abolition of the commissioning and prohibition of forced Indian labour. This was a major improvement for the natives, who now had rights that they did not have before, but still maintained the obligation of their work even if it was paid.

Repartimientos y encomiendas

From the beginning of the colonization of America, the problem of how to recruit native labor for the development of the new Hispanic society was raised. The new conquered territories were immense and the labor force was necessary to exploit all that fertile land. Obviously, at that time there were no temporary employment agencies or employment offices to manage employers’ employment needs. In addition, there were also no single job seekers. The settlers were not enough to carry out mining, agricultural or livestock works, so they had to turn to the natives and convince them to work for them. Moreover, the crown was very interested in producing these lands to collect the corresponding taxes as it was done with all the Castilian territories and subjects.

The settlers needed the work of the natives, but obviously they were not willing to give it to them. This meant for them a radical change in their way of life, mainly during the first years of the conquest in the Antilles islands, where they had a rather contemplative life, with subsistence crops and no economic or labour structure. For this reason, it was necessary to invent institutions that would facilitate this labor force and be able to start the colonial economy. However, in other more developed regions such as Mesoamerica and South America, existing labor institutions, such as the mita and yanaconazgo, were used to use this native labor force.

To this end, at the end of the 15th century, in the New World, the repartimiento, an institution of Castilian-Medieval origin, was implemented in the New World, which consisted of assigning land, lands and natives to a settler who had rendered some kind of service beneficial to the crown. Depending on the quality of this service and your needs, native speakers would be assigned to you. The first delivery was made in America Cristóbal Colón in 1496. The goods to be distributed were simply calculated and assigned to the settlers, who became their lifetime owners and had no liability or obligation arising from this donation. This selection was normally made by the same king, but in the American case it was delegated to the governor or the outgoing figure of the territory: governor, forward, mayor, etc. As a curiosity I would mention that in the first years of colonization, the number of indigenous people that a settler possessed was indicative of the power and wealth that he had, that is, it was a social scale data.

Many times the commission has been associated with this type of distribution, but no, they were different things, the commission was an institution also Castilian-Medieval installed in the New World later on. It was Governor Frey Nicolás de Ovando in 1505 who instituted it. Ovando arrived in Santo Domingo in 1502 with instructions from the Catholic Monarchs to treat the Indians well, respect their lands and work in fair conditions and with a salary to be paid. The problem that Ovando found was that even with these conditions the natives did not accept to submit to the commander and they fled quickly losing themselves to the mountains of the Spanish island. He also had to comply with the difficult royal order of suppressing the last distributions made by Columbus because he considered them unjust and abusive, which provoked the anger and disobedience of the colonists.

The basic difference between sharing and commanding was that in the former the settler had no obligation or duty to the native distributed, but in the latter there were a series of obligations and duties that they had to fulfil: teach him the Catholic religion, respect a series of breaks (delays) and pay him back in wages. It should be noted that the commission was a royalty, that is, a concession of the crown to his vassal, who was rewarded for his services. It was the latter that decided to whom, how much and for how long it was granted, so that it had full control of this institution, unlike the division in which there was simply a lifetime transfer of a property or person to the beneficiary.

The Burgos Laws of 1512

These systems of labour exploitation evidently resulted in numerous injustices and abuses. Despite the monarchs’ calls for good treatment of the natives, such as in own testament of Queen Isabel of Castile, there were acts of abuse and ill-treatment, derived from the defenselessness of the Indians. The protests quickly reached the ears of the kings at the hands of the religious who were on the islands and were witnesses, or said to be, of these events. The first to raise his voice loudly was the Dominican friar Antonio de Montesinos in the city of Santo Domingo with his well-known sermon on the fourth Sunday of Advent of 1511, in which he denounced these abuses in front of the same thing virrey Diego Colón and all the viceroyalty’s high officials. These facts reached the ears of the and Fernando el Católico who, faced with the insistence of the clerics, decided to convene a meeting of experts in the city of Burgos to legislate on these two important issues: the exploitation of labor of the Indian and the justification of the war to the Indians who did not collaborate.

Twenty sessions were held throughout the year and produced an important document which was originally called “Royal ordinances for the good regiment and treatment of the yndios” or Leyes de Burgos, which consisted of 35 articles regulating the regime of the Indians, their personal and working conditions, their rights and their recognition as men free of basic human rights, such as freedom and property. The Requirement, according to which before any act of conquest was carried out, the Indians had to be informed about the rights of the Castilian Crown and other matters that legitimized the conquest action they were about to face.

Las Ordenanzas or Granada of 1526

But the protests continued to come from the religious. In 1524 the Council of the Indies acquired full institutional autonomy from the Royal Council and its former president, Bishop Fonseca passed away and was replaced by the Dominican friar Fray García de Loaysa, who encouraged his brothers and sisters in the congregation to be even more vehement with the theme of the orders and the natives. The Council met in Granada in November 1526 and issued a provision on the 27th containing twelve ordinances addressed to the Spanish conquistadors in which they were invited to promote and encourage good customs to the natives in order to separate them from vices and instruct them in the Christian faith. Likewise, there was a call for responsibility and repentance for the injustices committed and the violent conquests were suspended, which did not involve advancing through those lands and taking possession of them, but always without harming or violating anything or anyone. These ordinances include details:

– The punishment of the conquistadors who abused the natives.

– The immediate liberation of the unjustly enslaved Indians.

– The obligatory presence of two clergymen in all military operations to ensure fair treatment of the Indians.

– Reading always the Request.

– The prohibition of Indian slavery.

– Military inclusion of evangelized Indians.

– Prohibition of indigenous labour in mines, fisheries and farms etc.

From that moment onwards, all the capitulations granted in the following years to the Spanish conquistadors would entail all these conditions to be fulfilled. The idea was to combine the freedom of the Indians with the need to entrust them to run the business, but under the control of the religious to avoid situations of abuse and mistreatment. But the problems persisted.

The New Indias Laws

All this previous legislation was a great advance at that time, in fact it is considered to be the predecessor of Human Rights. Never had a conquering kingdom or nation legislated in favor of the conquered natives and thus controlled and supervised the behavior of its own conquerors. The Karles I of Spain, saw that despite the already existing legislation applied continued to arrive in the mouths of religious like Bartolomé de las Casas news that the abuses and mistreatment of the natives continued and decided to act. In 1540 he convened a meeting of the University of Salamanca, headed by the professor in law and economics Francisco de Vitoria, to discuss all these facts and the legitimacy of the conquest and everything that was happening.

Francisco de Vitoria defended the natural right, that is, the existence of universal rights of all human beings that no person could eliminate, whether they were the Pope or the king of any kingdom. There was an interesting exchange of ideas and arguments with which to provide a basis for the new set of laws to be revised and established in the New World. This gave rise to the New Indian Laws that were promulgated on November 20,1542 in Barcelona. They consisted of 39 laws that were organized on these issues:

- >

- Laws 1 to 9: Restructuring of the Indian Council.

- Laws from 10 to 19: Creation of the Viceroyalty of Peru and two new Royal Audiences, the one in Lima and the one in the Confines (Guatemala).

- Laws of 20 to 33: Treatment due to indigenous people.

- Law 39: Reform of the tax system.

The New Indian Laws tried to stop the native demographic fall, which was a disgrace for all, and its economic consequences, as well as to guarantee the obedience of the Indians to royal power and not to the Spanish settlers who were forming a new social class, whose remarkable growth endangered even the very power of kings. These, despite the messages of loyalty and fidelity of the conquistadors, feared that they would obtain too much power and could be a danger to the unity of the Spanish crown. The way to halt possible attempts at independence was to take away their economic power and insert into these territories officials sent from the peninsula whose loyalty was well proven.

The most contentious laws were those concerning the regime of entrustments against which extreme rigour and the will to make them disappear. All the tasks of the viceroys, governors, bishops, monasteries, etc. are transferred to the Crown. Politically, the organizational norms of the Council of the Indies as an institution governing the New World are detailed, the territories are reorganized territorially, creating the Viceroyalty of Peru and the Royal Audiences of Lima and the Confines. From the social point of view proclaims the freedom of the Indians and eliminates the encomiendas. It also regulates the way in which new discoveries are to be made and how conquerors are to be rewarded. That is to say, it turned everything upside down and touched on very sensitive aspects, especially related to the Spanish conquerors and colonizers, such as the cargo and the new way of conquering.

New Indian Law Enforcement

The application of the New Indian Laws was very complicated. Many of them were a severe blow to the colonists’ way of life and, as expected, they did not cooperate in their implementation. In the newly created viceroyalty of Peru, let us remember that at that time it constituted all of South America except Venezuela, the commanding officers under the command of Gonzalo Pizarro and supported by the Real Audiencia de Lima joined forces to confront the first viceroy of Peru, Blasco Núñez de Vela, who tried to enforce the legislation strictly. Of a total of 5000 Spaniards registered in the Viceroyalty, only 400 were commenders, but with a magnificent economic and social power. These commissioners, through the town councils, expressed their displeasure and asked the viceroy to suspend the application of these laws and thus have a margin of time to send spokespersons to Spain to express their impracticability and request its modification.

But the viceroy stood firm and refused to listen to these complaints. Gonzalo Pizarro, brother of the discoverer and conqueror Francisco, who had achieved great power in the area and to whom the presence of a viceroy was shattering his old claim to be governor of Peru because it was so stipulated by the Capitulaciones de Toledo signed by his brother before the conquest of Peru. Under his hand joined the commenders and formed an important army to expel Núñez de Vela, something that they managed to overcome without struggle and very easily because he achieved very few followers, including the ears of the Royal Audience of Lima who tried to seize power but Pizarro controlled them and took over all the power of Peru. The viceroy was shipped to Spain but on his way to Panama he managed to liberate himself and disembarked in Tumbes where he formed a realistic army that was unable to stand up to the slate army in the battle of Añaquito near Quito, where he was defeated and executed on January 18,1546.

The defeat of the viceroy led to the suspension of the application of the New Laws in Peru. Gonzalo Pizarro was appointed governor of Peru creating a really dangerous situation for the Spanish crown, almost all of South America was at risk of being lost, even Pizarro sent one of his captains, Hernando de Bachicao, to Panama to take it and thus have absolute control of the entire subcontinent and the South Sea. But the king reacted quickly, on October 20,1545, by repealing several rules of the New Laws that stripped the rebellion of its foundations and appointed a new governor, the licensed Pedro de la Gasca, a man of great prestige within the Spanish crown for his intellectual and military skills. The Gasca marched to Peru without an army and only with the powers that the king had granted him to handle the situation in the most peaceful way possible: the capacity to pardon and the repeal of the most annoying laws of the New Laws.

When La Gasca arrived in Panama he was gathering support among the Spanish military personnel there and offering amnesty he managed to form an army to face Pizarro, who he finally defeated on April 9,1548 in the battle of Jaquijahuana. Here ended the adventure of Gonzalo Pizarro who was condemned for rebellion and executed together with his captains. In addition to ending this dangerous rebellion, La Gasca carried out numerous reforms and softened the application of the New Laws in order to reduce discontent and restore the loyalty of the king’s vassals.

In the viceroyalty of New Spain, the king sent a visiting judge, Francisco Tello de Sandoval, to announce and apply the New Laws. Evidently, just as in Peru, they provoked a deep malaise but in the Mexican zone there was no violence, but not in the Central American isthmus, where in Nicaragua, the Hernando and Pedro Contreras, who murdered Bishop Antonio de Valdivieso in 1550, rose up, friend of Bartolomé de las Casas, and responsible for implementing the new laws in that area attached to the newly created Royal Court of the Confines. With the exception of this sad fact, the visitator Tello de Sandóval, unlike the Peruvian viceroy Núñez de Vela, handled himself gently and tried to be conciliatory, and listened very attentively to the allegations of viceroy Antonio de Mendoza and the Royal Court of Mexico and decided to suspend the most annoying provisions and prepare a complaint to the Council of the Indies. In doing so, they managed to ensure that the orders were not eliminated and could continue to be inherited twice.

Download the New Indian Laws of 1542 in PDF format:

>.